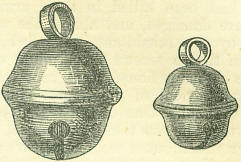

13th AugustBorn: Dr. William Wotton, author of Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning, 1666, Wrentham, Suffolk; Matthew Terrasson, jurist, 1669, Lyons; Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, eminent chemist, 1743, Paris; Adelaide, consort of William IV of England, 1792, Upper Saxony. Died: Tiberius II, Roman emperor, 582, Constantinople; Emperor Louis II, 875, Milan; Pope Sixtus IV, 1484; Francis Peek, antiquary, 1743, Godeby, Leicestershire; Henri Louis du Hamel, natural philosopher, 1782, Paris; Dr. Gilbert Stuart, historian, 1786, Musselburgh; Robert Plumer Ward, novelist, 1846. Feast Day: St. Hippolytus, martyr, 252. St. Cassian, martyr. St. Radegundes, queen of France, 587. St. Wigbert, abbot and confessor, about 747. AN EARTHQUAKE IN SCOTLANDEarthquakes are of very rare occurrence in the British Isles, or, at least, such as are of sufficient violence to attract attention. Scientific observers have not yet arrived at any very definite result as to the causes of these phenomena; but it is known that, when begun, they take the form of an earth-wave, propagated over a large area in a very small space of time. Observers in distant towns, frightened by what they see and hear, seldom can tell to a second, or even a minute, when these shocks occur; but if the times were accurately noted, it would probably be found that the shocks occur at consecutive instants along a line of country. Among the small number of recorded earthquakes in Great Britain, that of 1816 takes rather a notable place. At about eleven o'clock on the evening of the 13th of August, shocks were felt over nearly the whole of the north of Scotland. The Scottish newspapers gave accounts which, varying in detail, agreed in general results. From Aberdeen, a letter said: Where we sat, the house was shaken to the foundation; the heaviest articles of furniture were moved; and a rumbling noise was heard, such as if some heavy bodies were rolling along the roof. In many houses the bells were set ringing, and the agitation of the wires continued visible for some time after the cessation of the shock. It has been described to us, by one who was in Lisbon at that time, as exactly resembling the commencement of the earthquake in that city on the 6th of June 1807. This Aberdeen letter states that the shock lasted only six seconds, and seemed to travel from south-south-east to north-north-west. A letter from Perth said: Persons in bed felt a sensible agitation, or rather concussion, in an upward direction; and if the bed happened to be in contact with the wall, a lateral shock was also felt. In some houses, the chairs and tables moved backwards and forwards, and even the bells were set ringing. Birds in cages were thrown down from the sticks on which they were perched, and exhibited evident signs of fear. A writer at Montrose said: The leaves of folding - tables were heard to rattle; the fire-irons rang against the fenders, bells in rooms and passages were set ringing, in many kitchens the cooking utensils and dishes made a noise, and next morning many of the doors were found difficult to open. One gentleman observed his bookcase move from the wall, and fall back again to it.... Many leaped from bed, imagining their houses were falling; while others ran down stairs in great anxiety, supposing that some accident had happened in the lower part of their houses. In this neighbourhood, two excisemen, who were on the watch for smugglers, whom they expected in a certain direction, had lain down on the ground; and when the shock took place, one of them leaped up, calling to his companion: 'There they are, for I feel the around shaking under their horses' feet. Forres, Strathearn, Dingwall, the Carse of Gowrie, and other towns and districts, had a similar tale to tell. At Dunkeld, the liquor was shaken out of the glasses as a family sat at supper. At Dornoch, there was a mound crossing a narrow part of the Firth, with three arches at one end for small vessels to go under; those arches were thrown down. At Inverness, women fainted, and many were seen in the streets almost naked, calling out that their children had been killed in their arms. Many houses were damaged, and almost the whole were forsaken by the inhabitants, who fled under an impression that a second shock might occur. The walls of many houses were rent from top to bottom, and several of the largest stones thrown down on the roof.' One of the scared inhabitants declared, that 'he was tossed in his bed, as he had never been tossed out at sea, for full five minutes;' and other ludicrous misstatements of a similar kind were made. There is no evidence that any lives were lost. HAWKING IN THE OLDEN TIMEOf all the country sports appertaining to the upper classes during the middle ages, 'hawking may be fairly considered as the most distinctively aristocratic. It was attended with great expense; its practice was overlaid with a jargon of terms, all necessary to be learned by the gentleman who would fit himself for the company of others in the field; and thus hawking, in the course of centuries, became a semi-science, to be acquired by a considerable amount of patience and study. Hawking in Europe appears to have originated with the northern nations, and to have grown into importance along with themselves. The training of a hawk for the field was an essential part of the education of a young Saxon nobleman; and a present of a well-trained hawk was a gift to be welcomed by a king. Our Edward the Confessor spent the larger part of the time he did not consume in study in the sports of hunting or hawking; and Alfred the Great is reported to have written a treatise on the last-named sport. It was, however, those enthusiastic sportsmen, the early Norman kings and nobles, who carried the art to perfection, and established its rules and customs; inventing a language for falconry, and surrounding it with all the formalism of the stately rule of feudality. To be seen bearing a hawk on the hand, was to be seen in the true character of a gentleman; and the grade of the hawk-bearer was known also by the bird he bore. Thus, the gerfalcon was appropriated to a king; the falcon-gentle, to a prince; the falcon of the rock, to a duke; the peregrine-falcon, to an earl; the merlin, to a lady; and so on through the various ranks. The goshawk was permitted to the yeoman; the nubby, to a young man; while the ordinary serving men were allowed to practise with the kestrel. Priests were permitted the sparrow-hawk, but the higher clergy were, of course, allowed to use the birds pertaining to their rank; and their love of the sport, and pride of display, are satirised by many writers of their own era. In a poem on the evil times of Edward II, preserved in the Auchenleck MS. (Advocates' Library, Edinburgh), the author complains that These abbots and priors do again their rights, They ride with hawk and hound, and counterfeit knights. Piers Plowman is equally loud against their appearing with 'an heap of houndes at their heels;' and Chaucer says: They ride coursers like knights, With hawks and with hounds. In the reign of Edward III, the bishop of Ely attended the service of the church in the great abbey at Bermondsey, Southwark, leaving his hawk on its perch in the cloister; the hawk was stolen while there, and the bishop solemnly excommunicated the thieves. Had they been caught, they would have been rigorously treated by the laws, for their crime had been made felony. If a hawk was on any occasion lost, the finder was compelled to make it known to the sheriff of his county, that its noble owner might recover it, or the finder was liable to two years' imprisonment, and payment of the full value of the bird; if he could not do that, his punishment was increased. Fines also awaited such as carried hawks awarded by the laws of the chase to the use only of men higher in rank, and all kinds of protective restrictions surrounded the bird and the pastime. 'A knowledge of hunting and hawking was an essential requisite in accomplishing the character of a knight,' says Warton; and a gentleman rarely appeared in public without his hawk on his fist. The custom was carried to the extreme; and a satirist of the fifteenth century very properly censures such as bring their birds to church with them: Into the church there comes another sot, Without devotion strutting up and down, For to be seen, and shew his braided coat; Upon his fist sits sparrow-hawk or falcon. This constant connection of man and bird was in some degree necessitated, that it might know its master's voice, and be sufficiently familiar with, and obedient to him. It was laid down as a rule in all old manuals of falconry, that the sports-man constantly attend to the bird, feed him, and train him daily; and very minute are the rules laid down by authors who have, like Dame Juliana Berners, written on field-sports. To part with the hawk, even in circumstances of the utmost extremity, was deemed highly ignominious; and by the ancient laws of France, a knight was forbidden to give up his sword and his hawk, even as the price of his ransom.  The engraving on the right, copied from the book on field-sports, published in 1614, and entitled A. Jewell for Gentrie, gives us the full costume of a hawker, as well as a curious specimen of the fashion of the day. It represents King James I, as his majesty appeared in the field. He wears a high copatain hat and feather; a close-fitting jerkin, slashed and decorated with bands of lace; his breeches are in the very height of fashion, stuffed and padded to an enormous extent about the hip, tapering toward the knee, and covered with lace and embroidery. To his girdle is hung the large purse in which the hawker carried the implements necessary to the sport, or the hood and jesses removed from the hawk, which was perched on the left hand. This hand was protected from the talons of the bird by being covered with a thick glove, often highly enriched with needle-work and spangles. In his right hand the king carries a staff, which was used to assist the bearer when following the flight of the hawk on foot, in leaping a rivulet or ditch. Our Henry VIII had once a very narrow escape of his life when following his bird at Hitchin, in Hertfordshire. In jumping a ditch, the pole broke, and he fell head first into a mass of mud, which must have smothered him, had not one of his followers leaped in after him, and with some difficulty rescued him from his perilous situation. The dress of the hawk may now be described. It consisted of a close-fitting hood of leather or velvet, enriched with needle-work, and surmounted with a tuft of coloured feathers, for use as well as ornament, inasmuch as they assisted the hand in removing the hood when 'the quarry' (or birds for the hawk's attack) came in sight. A series of leathern and silken straps were affixed to the legs, to train the hawk in short flights, and bring him back to hand; or to hold him there, and free him entirely for a course at the game, by means of the jesses and tyrrits or rings. Othello uses a forcible simile from the practice of hawking, when speaking of his wife, he says: If I do prove her haggard, Though that her jesses were my dear heart-strings, I'd whistle her off, and let her down the wind, To prey at fortune. A small strap, fastened with rings of leather, passed round each leg of the hawk, just above the talons; they were termed bewets, and each of them had a bell attached. In a flight of hawks, it was so arranged that the different bells varied in tone, so that 'a consort of sweet sounds' might be produced. We engrave two specimens of hawk's bells of mixed metal, which were found in the mud of the Thames, and are still sonorous, one being an octave under the other.  The imagination kindles at the idea of a hawking-party going abroad on a cheerful April morning, over the pleasant fields around an English baronial castle, ladies and gentlemen riding gaily together, while their attendants followed, bearing the perches of the birds, and a motley throng would come after at a respectful distance, to get a peep at the sports of their betters. The aerial stage on which the play was played gave a peculiar elevation and liveliness to the scene. A sad affair it was for the poor herons and cranes of the neighbouring mores, but a right blithsome time for the gentlefolks who aimed at making them a prey. For the pacific King James, the sport had a fascination that seems to have thrown every other pleasure of life into the shade. In Heywood's curious play, entitled A Woman Killed with Kindness, 1617, is a hawking scene, containing a striking allusion to these bells. It is a vivid picture of country nobles at this favourite sport, and the dialogue is curious for the jargon of hunting-terms used in it. The following is as much of the scene as will assist the reader in reproducing, to 'his mind's eye,' the glories of the hawking-ground in the days of James I.: Sir Charles Mountford: So; well cast off: aloft, aloft! well flown! Oh now she takes her at the sowse, and strikes her down To th' earth, like a swift thunder-clap. Wendall. She bath struck ten angels out of my way! Sir Francis Acton: A hundred pound from me! Sir Charles. What, falconer? Falconer: At hand, sir! Sir Charles: Now hath she seiz'd the fowl, and 'gins to plume her; Rebeck: her not: rather stand still and check her. So, seize her gets, her jesses, and her bells: Away! Sir Francis: My hawk kill'd too! Sir Charles: Aye; but 'twas at the guerre, Not at the mount, like mine. Sir Francis: Judgment, my masters. Cranwell: Yours missed her at the ferre. Wendell: Aye, but our Merlin first had plum'd the fowl. And twice renew'd her from the river, too: Her bells, Sir Francis, had not both one weight, Nor was one semi-tune above the other: Methinks these Milan bells do sound too full, And spoil the mounting of your hawk. Sir Charles. 'Tis lost! Sir Francis: I grant it not. Mine likewise seiz'd a fowl Within her talons; and you saw her paws Full of the feathers: both her petty singles, And her long singles, grip'd her more than other; The terrials of her legs were stain'd with blood Not of the fowl only; she did discomfit Some of her feathers; but she brake away.'  The care necessary to the proper training of a hawk has already been alluded to. A continuous attention was given to a favourite bird, so that its natural wildness should be subdued, and it become familiar to its master. 'It can be no more disgrace to a great lord,' says Peacham, 'to draw a fair picture, than to cut his hawk's meat.' The hawk was trained to fly at the game, by means of a lure made in the shape of birds' wings, and partially formed of wing-feathers, inserted in a pad of leather or velvet, quilted with needle-work, and having a swivel-hook on the upper part, to which a long cord was attached; the lure being thrown upward in the air, and guided like a boy's kite; the hawk was trained to fly at, and strike it, as if it was a real bird; he was also trained at the same time to desist, and return to his master's fist, at his whistle. The bird could not get entirely away during this practice, as the long creance or string was appended to one leg by which he might be drawn back. The form of the lure is very clearly given in the wood-cut here copied from Geffry Whitney's Choice of Emblems and other Devises, printed at Leyden in 1586. This emblem typifies spes vana; and is thus quaintly elucidated by the author: The eager hawk, with sudden sight of lure, Doth stoop, in hope to have her wished prey: So many men do stoope to sights unsure: And courteous speech doth keep them at the bay. Let such beware, lest friendly looks be like The lure, to which the soaring hawk did strike! The practice of hawking appears to have suddenly declined in the early part of the seventeenth century. The expense and trouble of training the birds were great, and the improvement effected in firearms made shooting a more convenient and certain sport. Fowling-pieces of a light and elegant kind were manufactured, and to suit the tastes of the wealthy, were inlaid with gold and silver, or enriched by carving the stock with elaborate ornament in relief. 'The art of shooting flying' was cultivated with assiduity, giving a novel interest to field-sports, and hawking lost its charm for ever. The office of Grand Falconer of England is still a hereditary service of the crown, and held by the Duke of St. Alban's. The King's Mews at Charing Cross-the site of the building in which the king's hawks were kept while they mewed or moulted-has given a term to the English language, a stable-lane in any of our large cities being commonly called a mews-lane. |