12th MayBorn: John Bell, eminent anatomist, 1763, Edinburgh; Hon. General Sir George Cathcart, 1784; John Russell Hind, astronomer, 1823, Nottingham. Died: Thomas, Earl of Strafford, English minister, executed 1641, Tower-hill, London; John Rushworth, (historical collections), 1690, Southwark; Christopher Smart, poet, 1771, London; Francis Grose, antiquary, 1791. Feast Day: Saints Nereus and Achilleus, martyrs, 2nd century; St. Flavia Domitilla, 2nd century. St. Pancras, martyr, 304.; St. Pancras, after whom many churches are called, in Italy, France, and Spain, and whose name designates a parish in London having a population equal to many large cities, was a Roman youth of only fourteen at the time of his martyrdom under Dioclesian. THOMAS EARL OF STRAFFORDHe deserted the popular cause, to become one of the most noted instruments of Charles I in establishing an arbitrary government in England; he ruled Ireland with a rod of iron, and sowed the seeds of the great massacre in that kingdom. He was undoubtedly a great political culprit; yet the iniquitous nature of his trial and condemnation is equally undoubted; and every generous heart must sympathize with him when he found that the master he had served only too well yielded to sign his death-warrant. Political crime, too, is always so mixed up with sincere, though it may be blind opinion, that it seems hard to visit it with the punishment which we award to downright turpitude. The people made bonfires, and danced round them at his execution; but we, in a cooler time, may sigh over the idea of such a grand man being brought low on Tower-hill. When Strafford lay in the Tower, he wrote several letters to members of his family, marking the existence in that proud bosom of all the natural affections. To his wife he thus wrote, on receiving the charge preferred by his enemies: 'Sweet Harte,-It is long since I writt unto you, for I am here in such a trouble as gives me little or noe respite. The chardge is now cum inn, and I am now able, I prayse God, to tell you that I conceave ther is nothing capitall; and for the rest, I knowe at the worste his Majestie will pardon all without hurting my fortune, and then we shall be happy by God's grace. Therefore comfort yourself, for I trust the clouds will pass away, and that we shall have fine weather afterwards. Farewell!-Your loving husbande, Tower of London, 'STRAFFORD 4 Febr., 1641' The clouds did not pass away. The summer of 1641 was to be no summer for him. Less than a month before his death, when the bill for his attainder was passing to the House of Lords, he wrote in less confident, but still hopeful terms, to his little daughter: 'My dearest Nan,-The time, I trust, draws on when I may hope to see you, which will be one of the best sightes I can look upon in this world. Your father, as you desired, has been hearde speake for himself, now thee three weekes together, and within a few days we shall see the conclusion. Ther is, I think, little fear of my life; soe I hope for a meanes to be left me to let you see how deare and much esteemed you are and ever shall be to me. 'Look that you learns to play the good housewife, for now, perchance, there may be used of it; yet, however fortune befall me, I shall ever willingly give you the first good of it, and content myself with the second. 'My dear hearte,-Plie your book and other learnings, which will be of use unto you hereafter, and you will see how we will live happily and contentedly, and live to see all these stormes blowen over; that so, at leisure, and in fairer weather, I may tell that which I am, and must infallibly be, in all the conditions of life,-Your loving father, 'Tower, this 19th April, 1641. 'STRAFFORD.' FRANCIS GROSEFrancis Grose, the son of a rich Swiss jeweler settled in London-at one time an officer in the Surrey militia, whence it was he derived his epithet of 'Captain,'-noted personally for his Falstaff like figure, wit, and good-fellowship, was suddenly cut off by apoplexy at about the age of sixty. His voluminous works, depicting the ancient buildings of the three kingdoms, his treatises on military antiquities and on ancient arms and armour, may now be considered as superseded by better books; yet they were meritorious for their day. A huge, hearty, laughing figure he makes, through some twenty years of the last century; finally canonized in the verses of Burns, who was captivated by his good-humour, and wrote for him the wondrous tale of Tam o'Shunter. There were also some minor works by Grose, including one which embodied the slang and many of the curious local proverbs of England. In one of these lesser books he gives, apparently from his own observation in early life, a sketch of the small squire of England, as he existed before the days of modern improvement; it has something of the merit of Addison, and may be not inappropriately transferred, to these pages: THE COUNTRY SQUIREAnother character, now worn out and gone, was the little independent gentleman, of £300 per annum, who commonly appeared in a plain drab or plush coat, large silver buttons, a jockey cap, and rarely without boots. His travels never exceeded the distance of the county town, and that only at assize and session time, or to attend an election. Once a week he commonly dined at the next market town with the attorneys and justices. This man went to church regularly, read the weekly journal, settled the parochial disputes between the parish officers at the vestry, and afterwards adjourned to the neighbouring ale-house, where he usually got drunk for the good of his country. He never played at cards but at Christmas, when a family pack was produced from the mantel-piece. He was commonly followed by a couple of greyhounds and a pointer, and announced his arrival by smacking his whip, or giving the view-halloo. His drink was generally ale, except at Christmas, the 5th of November, or some other gala days, when he would make a bowl of strong brandy punch, garnished with a toast and nutmeg. A journey to London was, by one of these men, reckoned as great an undertaking as is at present a voyage to the East Indies, and undertaken with scarcely less precaution and preparation. The mansion of one of these squires was of plaster striped with timber, not unaptly called calamanco work, or of red brick, large casemented bow windows, a porch with seats in it, and over it a study; the eaves of the house well inhabited by swallows, and the court set round with holly-hocks. Near the gate a horse-block for the convenience of mounting. The hall was furnished with flitches of bacon, and the mantel-piece with guns and fishing-rods of various dimensions, accompanied by the broad-sword, partisan, and dagger, borne by his ancestors in the civil wars. The vacant spaces were occupied by stags' horns. Against the wall were posted King Charles's Golden Rules, Vincent Wing's Almanack, and a portrait ofthe Duke of Marlborough; in his window lay Baker's Chronicle, Foxe's Book of Martyrs, Glanvil on Apparitions, Quincey's Dispensatory, The Complete Justice, and a Book of Farriery. In the corner, by the fireside, stood a large wooden two-armed chair, with a cushion; and within the chimney corner were a couple of seats. Here, at Christmas, he entertained his tenants assembled round a glowing fire made of the roots of trees, and other great logs, and told and heard the traditionary tales of the village respecting ghosts and witches, till fear made them afraid to move. In the meantime the jorum of ale was in continual circulation. The best parlour, which was never opened but on particular occasions, was furnished with Turk-worked chain, and hung round with portraits of his ancestors; the men in the character of shepherds, with their crooks, dressed in full suits and huge full-bottomed perukes; others in complete armour or buff coats, playing on the bass viol or lute. The females likewise, as shepherdesses, with the lamb and crook, all habited in high heads and flowing robes. Alas! these men and these houses are no more; the luxury of the times has obliged them to quit the country, and become the humble dependents on great men, to solicit a place or commission to live in London, to rack their tenants, and draw their rents before due. The venerable mansion, in the mean time, is suffered to tumble down, or is partly upheld as a farm-house; till, after a few years, the estate is conveyed to the steward of the neighbouring lord, or else to some nabob, contractor, or limb of the law. THE PRENTICE'S PILLAR

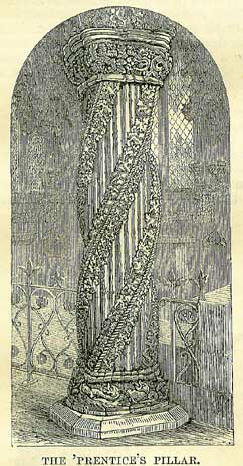

The beautiful collegiate church, commonly called chapel, of Roslin, near Edinburgh, which Britton allows to combine the solidity of the Norman with the finest tracery and ornamentation of the Tudor period, a gem of architectural beauty, and so entire that it has lately been refitted as a place of worship for an episcopalian congregation, used to be shewn, in the earlier years of this century, by a venerable crone named Annie Wilson, of whom a counterfeit presentment is here given, borrowed from the sober pages of the Gentleman's Magazine (September 1817). You obtained from Annie a sort of cottage version of the legends of the place: how the barons of Roslin were always buried in mail-how when any evil or death was about to befall one of them, 'the chaipel aye appeared on fire the nicht afore' - how Sir William Sinclair's dog saved his master's life by bringing down a stag 'afore it crossed the March-burn,' and all the puffy accounts of the former dignity of the Sinclairs of Roslin, which their relative, Father Hay, has put on record.  Mrs. Wilson also gave her numerous visitors an account, not quite in the manner of Pugin or Willis, of the details of the architecture-the site of the high altar-the 'star in the east' hanging from a drop in the groining over it-the seven acts of mercy and the seven deadly sins, carved on two lintels in the aisle-the legend on a stone, 'Strong is wine, stronger is the king, stronger are women, but above all truth conquers,-the mural tablet and epitaph of the Earl of Caithness, of the Latin of which she made sad havoc; all this in a monotonous voice, and without pauses, somewhat to the discomfiture of the hearers, who, however, never interrupted Annie with a question but they had reason to regret it, for she then recommenced her sing-song recital, and gave it all over again, it being impossible for her to resume the broken thread of her discourse. Mrs. Wilson's strong point was the Apprentice's Pillar. 'There ye see it, gentlemen, with the lace bands winding sae beautifully roond aboot it. The maister had game awa to Rome to get a plan for it, and while he was awa his 'prentice made a plan himself and finished it. And when the maister cam back and fand the pillar finished, he was sae enraged that he took a hammer and killed the 'prentice. There you see the 'prentice's face-up there in ae corner, wi' a red gash in the brow, and his mother greeting for him in the corner opposite. And there, in another corner, is the maister, as he lookit just before he was hanged; it's him wi' a kind o' ruff roond his face,' with a great deal more of the like twaddle, which Annie had told for fifty years without ever hearing a word of it doubted, and never once doubting it herself.    The 'Prentice's Pillar of Roslin is really a most beautiful specimen of Gothic tracery-a thing standing out conspicuously where all is beautiful. Viewing its exquisite workmanship, we need not wonder that such a story as that of the incensed master and his murder of the apprentice should be told regarding it. We have to fear, however, that, notwithstanding the faces of the master, the apprentice, and the apprentice's mother, exhibited on the walls, there is no real foundation for the tale. What chiefly gives cause for this apprehension is, that similar stories are told regarding particular pieces of work in other Gothic churches. In Lincoln cathedral, for example, there is a specially fine circular transept window, concerning which the verger tells you that an apprentice was the fabricator of it in the absence of his master, who, mortified at being so outdone, put an end to his own (not the apprentice's) existence in consequence. So also, in the cathedral of Rouen, there are two rose windows in the respective transepts, both fine, but one decidedly finer than the other. The guide's story is, that the master architect and his pupil strove which should plan the finest window. The pupil produced the north window, which proved 'plus belle que celle du midi,' and the humiliated master revenged himself by killing the pupil. We do not hear that in any of these cases there is any tangible memorial of the event, as at Roslin. How, it may be asked, should there be memorials of the event in that case, if the event be a fiction? We do not see that there is much force in this query. The faces, which are mere masks at the points in the architecture where such objects are commonly given, and not solitary objects (for there are two or three others without any story), may have been modified with a reference to the tale at a date subsequent to that of the building, or the apprentice's pillar and the faces together might all have been formed at the first, in playful or satirical allusion to similar stories told of previous Gothic churches. All who have ever visited the noble minster of Lincoln must remember the tomb of Bishop Fleming, whereon he is represented twice above in full pontificals, and below in the form of an emaciated figure encompassed in a winding-sheet. All, too, must remember the verger's tale regarding this worthy bishop of Wickliffite memory, to the effect that he died while making an attempt to imitate the Saviour in his miraculous fast of forty days. Every Lincolnshire clown has heard of the 'mon that doyed feasting,' and of whose final condition a memorial is presented on his tomb. Now the truth is that similar figures are to be seen in many churches-as, for example, on the tomb of Canon Parkhouse in Exeter cathedral,-on that of Bishop Tully, of St. David's, at Tenby, -on the tomb of John Baret, in the abbey church of Bury,-or that of Fox, bishop of Winchester, who died in 1528,-and always with the same story. Amongst well-informed persons no doubt is entertained that the story is a mere fiction of the plebeian mind, excogitated as a means of accounting for the extraordinary object presented to view. Such acts of ascetism are quite inappropriate regarding ecclesiastics of the fifteenth and 'sixteenth centuries. What was really aimed at was to give human pride a check, by showing what a great man was reduced to by wasting disease and the natural decay of extreme age. It was a sermon in stone. Another romantic story, 'representing how a young bride on her marriage-day sportively hid herself in an old oak chest, which closed down upon her with a spring-lock, and bow she was not discovered for many years after, by which time her husband had ended his life in melancholy fatuity,'-that tale which Mr. Rogers narrated so well in his poem Italy, and which a popular ballad has made still more familiar to the English public,-is, in like manner told in several places besides Modena. For example, there is a large old oaken chest in the possession of the Rev. J. Haygarth, rector of Upham, which is said to have formerly been in the neighbouring mansion of Marwell Old Hall, between Winchester and Bishop's Waltham,-where it proved a living tomb to a young lady, precisely in the like circumstances described by Mr. Rogers. Bramshall, Hampshire, has a similar chest and tale. The multiplicity of instances reveals the real character of the story, as one engendered by the popular mind in accordance with appearances. The chest is big enough to be a tomb for a human being: therefore it was so. The youth and bridal condition of the victim follow, as necessary to make the case the more telling. |