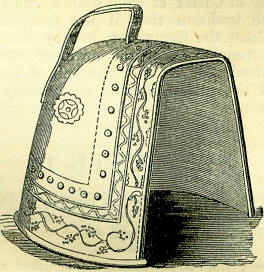

10th SeptemberBorn: Mungo Park, African traveller, 1771, Fowlshields, Selkirkshaire. Died: Louis d'Outremer, king of France, killed, 954; William the Conqueror, 1087, Rouen; John, Duke of Burgundy, murdered at Montereau, 1419; Dr. Edward Pococke, traveller and oriental scholar, 1691, Oxford; Dr. Thomas Sheridan, Irish scholar, translator of Persius, 1738; Mrs. Godwin (Mary Wollstonecraft), authoress of Rights of Woman, 1797, London; Ugo Foscolo, Italian republican and writer, 1827, London; Grace Aguilar, Jewish authoress, 1847, Frankfort. Feast Day: Saints Nemesianus, Felix, Lucius, another Felix, Litteus, Polianus, Victor, Jader, and Dativus, bishops, and their companions, part martyrs, and part confessors, 3rd century. St. Pulcheria, virgin and empress, 453. St. Finian or Winin, bishop and confessor, 6th century. St. Salvius, bishop of Albi, 6th century. St. Nicholas of Tolentino, confessor, 1306. THE END OF THE CONQUERORDuring his reign of twenty years subsequent to the Conquest, William had succeeded in planting his Norman followers and adherents upon the property of England. They might be described as an armed militia occupying the country, and owning a devoted allegiance to their sovereign for the lands they severally possessed. It was a grand position for a man to have achieved in a short lifetime; but it had been attained by pure violence, and was only upheld by force against the will of a noble though subjugated people. The Conqueror was, accordingly, not a happy man. He never felt any confidence in the continuance of the system of things which he had organised. He probably felt that he had been only a successful robber, and perhaps often envied the serener feelings of those whom he oppressed. While sojourning in Normandy, early in 1087, he addressed himself to the recovery from King Philip I of France of a piece of territory which had been appropriated by that sovereign some years before. He was at the same time submitting to medical regimen for the reduction of the extreme corpulence to which he had become subject. Philip put off his demand for the territory, and made a jest of the Conqueror's obesity. 'It is a long lying-in,' said he; 'there will doubtless be a ceremonious churching.' William, hearing of this speech, swore he would hold his churching at Notre Dame, in Paris, with ten thousand lances for tapers. He got up, and led an expedition of fire and sword into the French territory, feasting his eyes with the havoc and destruction which his soldiers spread around. It was while so engaged that his horse, chancing to plant his feet on some burning timber concealed by ashes, plunged and fell, causing a rupture in the belly of the overgrown king. He languished under this hurt for some weeks at Rouen, and fearing death, made some efforts to repair the cruel wrongs he had inflicted in the course of his life. He also made some arrangements regarding the fortunes of his children. On the 10th of September 1087, the great king breathed his last, in the sixty-first year of his age. William had only been feared, never loved. Now that he was no more, his servants and great officers thought only of their own interests. His body was left almost naked on the floor, and was buried by monks, without the presence of any relative, or any one who cared for the deceased. There being no coffin, and the body proving too large for the grave of masonry designed for it, it was necessary to force it down; in doing which it burst. Incense and perfumes failed to drown the stench thus diffused through the church, and the people dispersed in horror and disgust. Such was the end of one of the greatest potentates who ever lived-one who had driven human beings before him like cattle, but never induced any one to love him, not even one of his own children. LEGEND OF THE SONS OF THE CONQUEROROne day, it being observed that William was absorbed in deep thought, his courtiers ventured to inquire the cause of such profound abstraction. 'I am speculating,' said the monarch, 'on what may be the fate of my sons after my death' 'Your majesty,' replied the wise men of the court, 'the fate of your sons will depend upon their conduct, and their conduct will depend upon their respective characters; permit us to make a few inquiries, and we shall soon be able to tell you that which you wish to know.' The king signifying his approbation, the wise men consulted together, and agreed to put questions separately to the three princes, who were then young. The first who entered the room was Robert, afterwards known by the surname of Courthose. 'Fair sir,' said one of the wise men, answer me a question-If God had made you a bird, what bird would you wish to have been?' Robert answered: 'A hawk, because it resembles most a courteous and gallant knight.' William Rufus next entered, and his answer to the same question was: 'I would be an eagle, because it is a strong and powerful bird, and feared by all other birds, and therefore it is king over them all.' Lastly, came the younger brother Henry, who had received a learned education, and was on that account known by the surname of Beauclere. His choice was a starling, 'Because it is a debonnaire and simple bird, and gains its living without injury to any one, and never seeks to rob or grieve its neighbour.' The wise men returned immediately to the king. Robert, they said, would be bold and valiant, and would gain renown and honour, but he would finally be overcome by violence, and die in prison. William would be powerful and strong as the eagle, but feared and hated for his cruelty and violence, until he ended a wicked life by a bad death. But Henry would be wise, prudent, and peaceful, unless when actually compelled to engage in war, and would die in peace after gaining wide possessions. So when King William lay on his death-bed, he remembered the saying of his wise men, and bequeathed Normandy to Robert, England to William, and his own treasures, with-out land, to his younger son Henry, 'who eventually became king of both countries, and reigned long and prosperously. This story, which most probably is of Eastern origin, is frequently told under various circumstances by medieval writers. A Latin manuscript, of the thirteenth century, relates it in the following form: A wealthy English baron, whose broad lands extended over a large extent of England and Wales, had three sons; when lying on his death-bed, he called them to him, and said: ' If you were compelled to become birds, tell me what bird each of you would choose to resemble?' The eldest said: 'I would be a hawk, because it is a noble bird, and lives by rapine.' The second said: 'I would be a starling, because it is a social bird, and flies in coveys.' The youngest said: 'I would be a swan, because it has a long neck, so that if I had anything in my heart to say, I should have plenty of time for reflection before it came to my mouth.' When the father had heard them, he said to the first: 'Thou, my son, as I perceive, desirest to live by rapine; I will therefore bequeath thee my possessions in England, because it is a land of peace and justice, and thou canst not rob in it with impunity.' To the second, he said: 'Because thou lovest society, I will bequeath thee my lands in Wales, which is a land of discord and war, in order that thy courtesy may soften down the malice of the natives.' And then turning to the youngest, he said: 'To thee I bequeath no land at all, because thou art wise, and will gain enough by thy wisdom.' And as he foretold, the youngest son profited by his wisdom, and became Lord Chief-Justice of England, which in those times was the next dignity to that of king. DR. THOMAS SHERIDANOn the 10th of September 1738, Dr. Sheridan was sitting, after dinner, in the house of a friend. The conversation happening to turn on the force and direction of the wind, Sheridan said: 'Let the wind blow east, west, north, or south, the immortal soul will take its flight to the destined point;' and leaning back in his chair, instantly expired. Dr. Sheridan was the intimate friend and choice companion of Jonathan Swift; the father of 'Manager Tom,' as his son was termed in Ireland; and the grandfather of the Right Honourable Richard Brinsley Sheridan. He was born in the county of Cavan, about 1684, and, having completed his education at Trinity College, set up a classical school in Dublin. Entering into orders, he received the degree of D.D., and was appointed to a church-living in the south of Ireland. But by a singular act of inadvertence, he lost all chance of further preferment, by preaching a sermon on the anniversary of George I's birthday, from the text: 'Sufficient for the day is the evil thereof.' On this becoming known, he was struck off the list of the Lord-Lieutenant's chaplains; parents hastened to take their children from his school; and, in short, as Swift said: 'He had killed his own fortunes by a chance-shot from an unlucky text.' No reverse of fortune, however, could damp or discourage the high spirits of Dr. Sheridan. Such, it is said, was his perpetual flow of ready wit and humour, that it was impossible for the most splenetic man to be unhappy in his company. When Swift, in a morbid state of disappointment, was condemned to live, as he considered it, an exile in Ireland, the companionship of Sheridan formed the great solace of his life. For one whole year they carried on a daily correspondence, and, according to previous stipulation, each letter was the unpremeditated effusion of five minutes' writing. Some of the funny nonsense thus composed, is preserved in Swift's miscellaneous works, though the greater part has fallen into merited oblivion. Dr. Sheridan was an excellent classical scholar, and wrote a prose translation of Persius, which was published after his death. Though indolent, good-natured, careless, and not particularly strict in his own conduct, he took good care of the morals of his scholars, whom he sent to the university well grounded in classical lore, and not ill instructed in the social duties of life. He was slovenly, indigent, and cheerful, knowing books better than men, and totally ignorant of the value of money. Ill-starred, improvident, but not unhappy, he was a fiddler, punster, quibbler, and wit; and his pen and fiddle-stick were in continual notion. As might be supposed, Sheridan's house, at Quilca, was such as Swift has described it in the following lines; and the writer may add, that, in his youth, he often saw the menage of an Irish gentleman and scholar, to which the same description would be as justly applicable. QUILCA Let me thy properties explain: A rotten cabin dropping rain; Chimneys with scorn rejecting smoke; Stools, tables, chairs, and bedsteads broke. Here elements have lost their uses, Air ripens not, nor earth produces; In vain, we make poor Shela toil, Fire will not roast, nor water boil; Through all the valleys, hills, and plains, The goddess Want, in triumph reigns, And her chief officers of state, Sloth, Dirt, and Theft, around her wait. UGO FOSCOLOFifty years ago, the name of Ugo Foscolo, now well-nigh forgotten, enjoyed as extensive a reputation as that of the most enthusiastic champion of Italian independence, and one of the greatest and brightest ornaments of modern Italian literature. What he actually effected, however, in the first of these characters, was but trifling, and in the second, he has left little, not even excepting his celebrated Letters of Jacopo Ortis, which can commend itself to the tastes of this practical and unsentimental age. He was descended from a noble Venetian family, and was himself born on board a frigate, lying off the island of Zante, of which his father was governor for the republic of Venice. Entering life as a young man, just when the French Revolution was stirring the social life of Europe from its very depths, young Foscolo ardently embraced the new doctrines, and became so conspicuous a maintainer of them, that he was arrested and carried before the terrible inquisition of state, as a partisan in a conspiracy for overthrowing the government. No proof, however, appeared against him, and he was acquitted. It is related that his mother, a Greek lady, on seeing him led off as a prisoner, exclaimed to him, in a spirit worthy of a Spartan matron of old: Die; but do not dishonour thyself by betraying thy friends! After gaining considerable renown by the representation of his tragedy of Tieste, when he was yet little more than twenty, he received the appointment of secretary to Battaglia, the Venetian ambassador to Bonaparte. The treacherous manner in which the latter transferred the republic to Austria, disgusted him for a time with political life, and he retired into Lombardy, then styled the 'Cisalpine Republic,' and penned there his celebrated romance, entitled Ultime Lettere di Jacopo Ortis. This created nearly as great a sensation as Goethe's Sorrows of Werter, to which, in point of subject-matter and style, it is very similar, though differing from it in the amount of political allusion by which Foscolo's work is throughout characterised. It has been translated into various languages, and contains much beautiful and pathetic writing, but imbued with an extremely morbid spirit. Emerging from his retreat, Foscolo again sought the busy world, and served for some years in Bonaparte's army; but finding himself obnoxious to the authorities, on account of his republican principles, he resigned his commission, and returned once more to private life. Various literary works, including his edition of the writings of General Montecuccoli, and a translation of the first book of the Iliad, now occupied his leisure, and about 1809, he was appointed professor of literature in the university of Pavia, where the spirited style of his lectures to the young men so alarmed the sensitive absolutism of Bonaparte, that, in two months afterwards, the three Italian universities, Pavia, Padua, and Bologna, were closed. On the restoration of the Austrian government, Foscolo was suspected of being accessory to a conspiracy for its overthrow, and found it expedient to retire, first to Switzerland, and then to England, where he took up his abode for the remainder of his days. Such are the leading events in the history of the Mazzini and Victor Hugo of his day. While in England, he enjoyed ready access to the first society in the metropolis, being both a man of great classical attainments, and most brilliant conversational powers. He built for himself a cottage in the neighbourhood of the Regent's Park, which, in allusion to the controversy on the use of the digamma in Greek, and his own large share in the dispute, he christened 'Digamma Cottage.' The furniture and decorations of his habitation were of the most magnificent order, including casts of the most celebrated works of sculpture, which were scattered through every apartment, and were contemplated by their owner with an enthusiasm little short of adoration. In excuse for this lavishness, he would observe, in reference to his costly articles of furniture: They encompass me with an air of respectability, and they give me the illusion of not having fallen into the lowest circumstances. I must also declare, that I will die like a gentleman, on a clean bed, surrounded by the Venuses, Apollos, and the Graces, and the busts of great men; nay, even among flowers, and if possible, while music is breathing around me. It is easy to infer from this that Foscolo had much of the Epicurean in his composition. He is said, however, to have been remarkably abstemious in his habits, and laid claim himself to vying with Pythagoras for sobriety, and Scipio for purity of morals. Unfortunately, his means, eked out as they were by writing for the various reviews, and publishing essays on Petrarch, and a commentary on Dante, proved wholly inadequate to the maintenance of the luxurious style of living which he affected; and, after a brief period, the temple which he had reared to the Graces, with its gorgeous appliances, was brought to the hammer. His latter years were sorely disturbed by pecuniary embarrassment, a source of vexation which was greatly aggravated by a violent and fretful temper. He seems, indeed, to have been both true and generous hearted; but, as even an intimate friend admitted, his virtues were those of a savage nature. When in good-humour and spirits, nothing could be more entertaining than his conversation, though he displayed great peevishness if any irrelevant question were asked. He used to say: 'I have three miseries-smoke, flies, and to be asked a foolish question.' MARY WOLLSTONECRAFTIt is impossible for human laws to do more than minister to the greatest good of the greatest number; no skill can avert their oppressive action in singular cases. The law decrees that the contract of marriage shall only terminate with the decease of either partner, and few will dispute, that the law decrees wisely. But there are cases-and we do not allude to those in which divorce is the permitted remedy-where life-long marriage is life-long misery; yet, for the relief of such sufferers no thoughtful legislator advocates the abrogation of a law which, in its broad sweep, affords assured protection and security to the weaker half of humanity-to wives and children. Again, the law consigns children to the absolute government of their parents, and though there are many who neglect and abuse their trust, yet we feel that it is better to tolerate partial wrong, than invade an order which, on the whole, coincides with the greatest good of the greatest number. So, again, we permit the spendthrift to waste and the miser to hoard rather than infringe on that sense of independence and ownership, which more than doubles the joy of possession and gives spur and purpose to enterprise. Similar illustrations of exceptional sufferings and mischiefs might be multiplied indefinitely, for wherever there is a just and kind law, there is, at the same time, a possible shelter for injustice and cruelty. Whoever, therefore, will defend the best law, must be content to prove its general, not its universal excellence. This truth is continually forgotten by enthusiastic and generous natures. They encounter some case of hard-ship under the law, and at once raise a cry for its modification or abolition, never considering, whether if the cord were relaxed on one side it might not cut deeper and more dangerously on the other; and sometimes not satisfied with their verbal protest, they enter into actual rebellion, and in their own persons endure social obloquy and outlawry, in the vain endeavour to compass a universal, a Utopian justice. Among the boldest and noblest of such mistaken innovators must be ranked Mary Wollstonecraft. She was born on the 27th of April 1759, but whether in London or Epping Forest, she could never ascertain. Her father was the son of a Spitalfields manufacturer, from whom he inherited about £10,000: her mother was an Irishwoman, a Miss Dixon of Ballyshannon. Mr. Wollstonecraft was a rolling stone which not only gathered no moss, but wore away its substance in rolling. He moved from London to Yorkshire, and from Yorkshire to London, and thence to Wales, sometimes farming and sometimes trading, and always losing. His temper was abominable; when in a rage, he would strike his wife, flog his children, and kick his dogs, finishing up with a fit of maudlin affection. Mary had frequently to throw herself between her father and mother to save her from his blows. Regular education was out of the question under these circumstances, and the young Wollstonecrafts were left to pick up what learning they could at a variety of day-schools. Mary was a handsome girl, lively and intelligent, with a proud spirit and ardent affections. For dolls and needle-work she had a thorough contempt, prefer-ring to join in the sports of her brothers. Among the wanderings of the family, they settled for a while at Queen's Row, Hoxton, in the neighbourhood of which William Godwin was a student at the Dissenters' College. Reflecting, in after-years, on his unconscious proximity to Mary, he observes: It is perhaps a question of curious speculation to inquire, what would have been the amount of difference in the pursuits and enjoyments of each party had they met, and considered each other with the same distinguishing regard in 1776, as they were afterwards impressed with in the year 1796. While at Queen's Row, Mary made the friendship of Frances Blood, a young lady of many accomplishments, who inspired her with a fervent desire for intellectual improvement. Tired of her wretched home, she became companion to Mrs. Dawson, a lady of Bath, who was reputed to have such a temper that no one could abide with her. Mary forewarned was forearmed; she stayed with the virago two years, taught her better manners, and only left her side to nurse her mother in a mortal illness. Her next important step in life was to open a school in Islington, in company with her sisters and Frances Blood. Mary proved an excellent teacher; the school flourished, and was removed to Newington Green. Near by lived Dr. Price, who became a visitor, and Mary's cordial friend. She was introduced to Dr. Johnson, but his death prevented further acquaintance. Just as life was growing prosperous, Miss Blood fell into a decline, and was ordered to Portugal. Hearing that there was no hope of her recovery, Mary, in the strength of her affection, left the school to its fate, and sailed for Lisbon that she might be near her dear companion in her last hours. On her return, she went to Ireland as governess in the family of Lord Kingsborough, and there won golden opinions for her intelligence and amiability. One of her pupils, Countess Mount Cashel, remained Mary's friend through good and evil report till death divided them. Conscious of powers which as yet had found no outlet, Miss Wollstonecraft came to London in August 1787, with the daring hope of acquiring a livelihood by authorship. The year before, she had made her advent in the world of letters by the publication of Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, for which her publisher, Mr. Johnson, had given her ten guineas. She took humble lodgings in George Street, Blackfriars Bridge, and set to work. She contributed largely to the Analytical Review; abridged Lavater's Physiognomy; translated from the German Salzmann's Elements of Morality; from the French, Necker's Importance of Religious Opinions; and from the Dutch, Young Grandison; wrote tales for children, and executed a variety of other literary business: and not only did she earn her own living, but was able to assist her father, fund situations for her brothers and sisters, and adopt an orphan girl of seven. In such labours she might have spent many years in comparative obscurity, had not Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in November 1790, stirred in her such indignation, that she determined to answer the recreant Whig. She brought out a Vindication of the Rights of Man, in which she trounced her adversary with no little vehemence and much natural eloquence. It was among the first of the many replies to which Burke was treated, and it had a very large sale. Miss Wollstonecraft from that hour was a marked woman. By one set she was regarded with horror as a sort of monster, and by another was extolled as a divinity. Unhappily, her admirers stimulated her worst tendencies, and provoked her to issue a Vindication of the Rights of Women, wherein much that was true and excellent was nullified by extravagant sentiment and language. Her increased income allowed her, in 1791, to remove to better apartments in Store Street, Tottenham Court Road, where she was visited by the most distinguished republicans and freethinkers of that sanguine age. Godwin then met her for the first time at a dinner-party where Thomas Paine was present, and disliked her. Paine was not much of a talker, and the little he had to say Godwin was anxious to catch, but Mary interrupted his purpose by her almost incessant conversation. Along with Godwin she had begun to entertain the opinion that marriage was an unjust monopoly; that marriage ought only to exist as long as there was heartfelt sympathy between a husband and wife; and that wherever that sympathy sprung up, the licence of marriage should be allowed. Poor Mary was doomed, in her own person, to illustrate the peril to women that lay in such a creed. Her first attachment was to Fuseli, the painter. A lively affection developed between them, but Mrs. Fuseli, like a dragon, lay in the way, and Mary, as a diversion to her feelings, made a trip to Paris, which extended into a residence of two years. By Paine she was introduced to the principal revolutionary leaders, and found a congenial spirit in Helen Maria Williams. From her window she saw Louis XVI pass in a hackney-coach to execution, 'with more dignity,' she wrote, 'than I expected from his character.' Whilst in the spring of her enjoyment in Paris, she met Gilbert Imlay, an American merchant, and put in practice her theory by living with him as his wife without the legal forms of matrimony. All for a time went on smoothly. In a pleasant retreat at Neuilly she worked industriously on her most finished work, A Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution. Imlay left her nominally for a few weeks to look after some business at Havre. One day, on entering Paris, she passed the guillotine, whilst the blood streamed over the pavement. She burst at once into loud exclamations of horror and indignation. A kind bystander checked and implored her to hasten and hide herself from all who had heard her words. The agony she experienced on being informed of the death of Brissot, Vergniaud, and the twenty deputies, she vowed was greater than any pain she had ever felt. Meanwhile Imlay did not return. She followed him to Havre, and there gave birth to a daughter, named Frances, in memory of her old friend, Miss Blood. Imlay then went to London, persuading his wife to return to Paris, with the promise that he would rejoin her shortly. Half a year elapsed, but no Imlay made his appearance. Anxious and suspicious, Mary crossed to England, and arrived in London to find her worst fears realised, and the father of her child in the arms of another mistress. She prayed that he would return to her, and was only prevented committing suicide by his timely arrival. By renewed seductions he induced her to start for Norway, and there transact some business for him. He made an assignation at Hamburg, which he did not keep, and on her return to London, it became at last apparent that she was betrayed and befooled. Distracted with anguish, she took a boat to Putney, and walking about in the rain till her clothes were drenched through, she leaped over the bridge into the Thames. Happily, she was observed and rescued. Again she saw Imlay, and made the extraordinary proposal that she and his paramour should live together. 'I think it important,' she wrote to him, 'that you should learn habitually to feel for your child the affection of a father.' Imlay, who seems to have been an irresolute scoundrel, at first assented and afterwards refused, and Mary then summoned up resolution, and dismissed him from her thoughts for ever. Well-nigh broken-hearted, she went to live in Pentonville, and renewed her acquaintance with Godwin. Acquaintance melted into friendship, and friendship into love, and again she ventured to become a wife without the ceremonies of marriage. Finding, however, the pains and penalties attached to such a relation unendurable, they yielded to what they thought popular prejudice, and were married. Godwin's account of the method of their conjugal life is worth reading. He writes: Ours was not an idle happiness, a paradise of selfish and transitory pleasures. It is perhaps scarcely necessary to mention, that, influenced by the ideas I had long entertained on the subject of cohabitation, I engaged an apartment about twenty doors from our house in the Polygon, Somers Town, which I designed for the purpose of my study and literary occupations. Trifles, however, will be interesting to some readers, when they relate to the last period of the life of such a person as Mary. I will add, therefore, that we were both of us of opinion, that it was possible for two persons to be too uniformly in each other's society. Influenced by that opinion, it was my practice to repair to the apartment I have mentioned as soon as I rose, and frequently not to make my appearance in the Polygon till the hour of dinner. We agreed in condemning the notion, prevalent in many situations in life, that a man and his wife cannot visit in mixed society but in company with each other, and we rather sought occasions of deviating from, than of complying with, this rule. By these means, though for the most part we spent the latter half of each day in one another's society, yet we were in no danger of satiety. We seemed to combine, in a considerable degree, the novelty and lively sensation of a visit, with the more delicious and heartfelt pleasures of domestic life. This philosophic union, to Godwin's inexpressible affliction, did not extend over more than eighteen months. Mrs. Godwin died in childbed, on the 10th of September 1797, at the age of thirty-eight. Her infant grew to womanhood, and became the wife of the poet Shelley, and the author of Frankenstein. The errors of Mary Wollstonecraft's life lie on the surface, and many will be quick to supply the ready commentary of condemnation. If, however, we are more careful to be just than vindictive, we shall not leave her without many allowances, some admiration, and much pity. Considering the unhappy circumstances of her childhood, and her imperfect education, we shall regard with wonder and respect the energy and self-control by which she transformed herself into the successful schoolmistress, the governess, the writer for the press, the antagonist of Burke, and the esteemed associate of politicians and philosophers. Nor shall we forget her generosity, almost wild in its excess; her free sacrifice of money and opportunity to her family and friends. Nor shall we fail to observe that the painful eccentricities of her career were confined within seven years, 1790-1797; a time of abnormal excitement, when the mind of Europe broke loose from the moorings of ages, and every maxim of law and morals was put to inquisition. Mary Wollstonecraft found herself in this maelström of revolution, and determined to realise that new moral world about which so many were content to theorise. Godwin himself bears witness that she did not reason, but darted to conclusions. In the matter of her cohabitation with Imlay and Godwin, she must receive the full benefit which charity accords to those who, do wrong believing they do right. In her conduct there was nothing clandestine; indeed, she took superfluous pains to inform her acquaintance that she was not legally married, and thus drove from her presence many who were very willing to enjoy the charm of her society, if only she would condescend to subterfuge. INCIDENTAL TO A JOURNEY TO PARIS IN 1723On the 10th of September 1723, three English gentlemen, named Sebright, Davis, and Mompesson, set out from Calais for Boulogne, on their way to Paris. Sebright and Davis travelled in one coach, Mompesson and a servant in another: another servant rode on horseback. Before leaving the Lion d'Argent hotel in Calais, Mr. Sebright changed twenty-five guineas into French silver money, for the use of the party on the road. Hence, it was supposed, the sad accident which overtook them in their journey. About seven miles from Calais, they were beset by six mounted highwaymen, who demanded the money they were believed to have in their possession. The English gentlemen, having no arms but their swords, made no resistance. All the money they possessed, being about one hundred and twenty pounds, was surrendered, as also their swords, watches, and other trinkets. They were commanded to come out of the chaises, and lie down with their faces to the ground, and when their persons had in these circumstances been more effectually searched, the word to kill was given, and the whole five were then shot and hacked in the most cruel manner. Another English gentle-man, named Locke, coming up at the moment on his way from Paris, was shot in his vehicle, and with difficulty his Swiss valet was enabled to beg his life. When the murderous work appeared to be complete, the six banditti rode off with their booty. It then appeared that Mr. Mompesson, not-withstanding his throat had been cut, was still alive; and so was Mr. Sebright's servant, Richard Spendelow. But the unfortunate gentleman survived only a few hours. Six persons in all lost their lives on this occasion. It was supposed that the incident of the changing of the twenty-five guineas was what attracted the attention of the predatory party to the travellers. We do not learn that more than one person was ever brought to justice for this horrid outrage, notwithstanding that the Regent d'Orleans offered large rewards for their apprehension.' THE CURFEWThe lengthening evenings bring naturally to our minds their discomforts in the olden times, and the various customs and observations connected with them. Among these was the curfew-bell, which has been made well known to all ears by the frequent allusions to it in our poets, but which has been the subject of not a few 'vulgar errors.' In those old times, people, in general, possessed nothing like clocks or watches; they learned, by the practice of observation, to judge roughly of the time of the day, but in cases where it was necessary to know the exact hour, they were entirely at a loss. Any implement for measuring time was rare, and belonged only to a public body, or institution, or to some very remarkable individual, and the only means of imparting to the public the know-ledge gained from it, was by ringing a bell, or blowing a horn, at certain hours of the day. This practice was first introduced in the monastic establishments, where the inmates required to know the hours for celebrating the various services. It was probably adopted also in the great houses of the aristocracy, and in towns. There were, in fact, many customs to be observed at stated hours, besides the religious services, and some of these were required by public safety. In the middle ages there was a very much larger proportion of society which lived by cheating, plundering, and ill treating the rest, than in modern times. Owing to the want of any effective police, there was no safety out of doors at night; and even people who, by daylight, appeared to live honestly, sallied forth after dark to rob and assassinate. It was attempted, in towns especially, to meet this evil, by making it criminal to be found out of doors after a certain hour; and, as otherwise offenders might plead ignorance, it was ordered that the hour should be publicly sounded, generally by the town-bell, and when that was heard, all people were compelled to shut the doors of their houses, put out their fires, and retire to bed, those who were out of bed after the sounding of the bell being liable to severe punishment. It was an efficacious way of clearing the streets. The bell sounded for this purpose was, in France, called popularly the couvre-feu, or cover-fire, which, in the Latin documents in which it was alluded to, was translated by ignitegium. Something of the same kind,  probably, existed in the Anglo-Saxon times, but the name just mentioned was, of course, introduced by the Normans, and we have no express allusion to the practice in this country before the Anglo-Norman period. Hence, no doubt, has arisen the erroneous notion that the couvre feu bell, corrupted into the curfew-bell, was invented by William the Conqueror as an instrument of tyranny. It was, apparently, a municipal and not a state institution, and the utility of a general covering of fires at a reasonable hour is obvious. In those days, most houses were constructed wholly or mostly of wood, and were extremely liable to take fire when fire was used carelessly. To cover up the fire was an important regulation for safety, and a utensil was employed for the purpose-here represented. The curfew-bell was used in the monastic establishments as well as in the towns. In the great abbey of St. Alban's, it was ordered that the monks should not remain assembled in conversation after the ringing of the curfew-bell. In Lichfield Cathedral, according to the statutes of that church, quoted in Ducange, the curfew-bell was sounded at seven o'clock in the evening, and this appears to have been the usual hour at the earlier period, for ordinary people went to bed very early, and rose before daybreak; but in course of time, seven o'clock seems to have been thought too early, and it was moved onwards an hour to eight o'clock, which seems, down to a very late period, to have been the most common hour of the curfew in England, though in many places it was still further advanced to nine o'clock. The curfew is still rung in many towns and parishes in England, in some at eight o'clock, and in others at nine. At the end of the last century, as we learn from the Gentleman's Magazine for 1790, the curfew was announced at the latter hour at Ripon, in Yorkshire, by a man with a horn, which he blew, first at the market-cross, and then at the mayor's door. In Scotland, the hour of curfew was similarly retarded, until it was fixed, not at nine, but at ten o'clock, and that seems to have been, in later times, the usual hour of the Scottish curfew. It is quite a mistake to suppose that the curfew-bell was peculiar to this island-it was a natural expedient for serving a generally useful purpose, and was adopted in France, Italy, and Spain, and probably in all parts of continental Europe. More-over, a corresponding bell was rung in the morning, to inform people of the hour at which it was customary to rise. In some instances, this is merely said to have taken place at daybreak, but a more usual hour appears to have been four o'clock in the morning. At Ludlow, in Shropshire, this bell still rings at six o'clock, and the evening-curfew at nine. It is kept up merely because it has been customary, and because there is provision for it in the old corporation or parish orders. At London, as we learn from records of the end of the fifteenth century, the curfew was sounded at the same time from the three churches of Bow in Cheapside, St. Bride's, and St. Giles's without Cripplegate, and the clerks of all the other parish churches in the metropolis were obliged to begin ringing the moment they heard one of these, or, for neglect, were to be presented to the quest of wardmote. At Oxford, the curfew was rung at Carfax at eight o'clock, and there was a foolish tradition that it was established, not by William the Conqueror, but by King Alfred. Here, a refinement of the ordinary curfew had been introduced, for, after the bell of Carfax had sounded the curfew, it rung deliberately the day of the month. |